A WALKING TOUR OF CIVIL WAR MELBOURNE

By

Barry J Crompton

Melbourne

January 2012

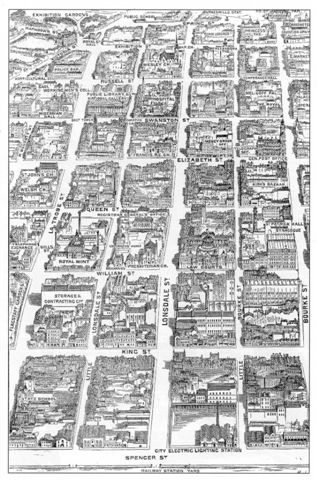

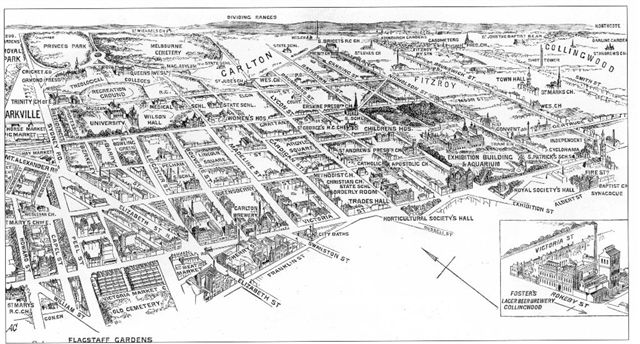

We could have a walk to St Kilda, Prahran, South Yarra, Brighton or Sandringham, we could do another one to Kew, Hawthorn, Richmond and Collingwood; we would also do Footscray, Yarraville and Sunshine but today let's concentrate on Collins Street, Melbourne.

We start at the top of the city in Spring Street - on the left is the Treasury Building, the depository for the gold that was Victoria's (and Melbourne's) reason for the huge increase of population that made us the largest city in the southern hemisphere at the time of the Shenandoah's arrival.

Next door to the Treasury Building is Parliament House, the seat of government. One of the members, Peter Lalor, had three brothers fighting in the Union army and another member had an uncle and cousins who fought for the Confederacy.

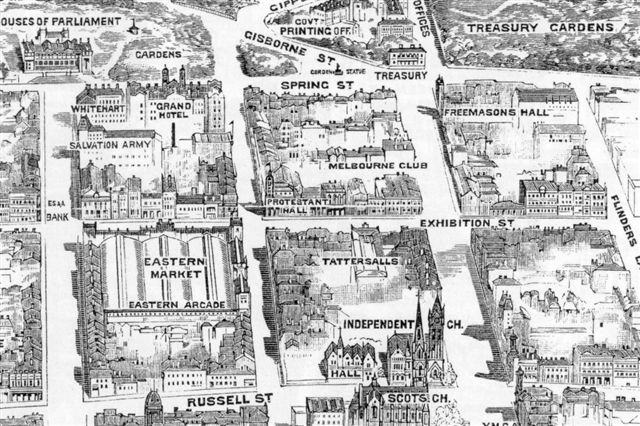

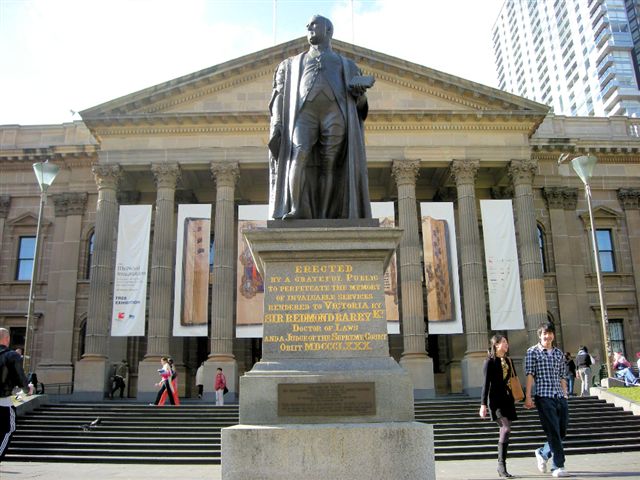

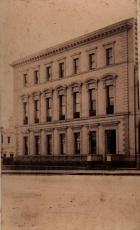

A short walk down the road sees the Melbourne Club where one of its residents, Captain Standish (who originated the Melbourne Cup horse race in 1861 when Archer won, the same year as the start of the Civil War); the government also had long debates on the record of the Shenandoah. The Melbourne Club hosted a dinner in the officer's honour (amongst the guests we think is Sir Redmond Barry, who planned the State Library and hung Ned Kelly); opposite the Melbourne Club now is the Sofitel Hotel and at the Flinders Lane side of the building was the photographic studio of Batchelder and O'Neill where the Shenandoah officers had their photographs taken; go the same distance down to Flinders Street and you'll be at one of places listed as a recruiting station.

With our soggy beer mat on a stick to lead us on, we continue walking down Collins Street; past Exhibition Street (at the stage still called Stephen Street - only renamed after 1885 when the 50th anniversary of the founding of Melbourne was commemorated and the U.S. consul in 1885 was ex-Confederate naval officer James Morris Morgan). On the corner of Exhibition and Bourke Street was the Alhambra Dance hall where one of the Confederate officers stayed overnight after he missed his lighter back to the ship. The building in the 1970's when I first remembered it was a branch of the National Australia Bank, was then an art gallery and is now as of 2011 a checken fast food outlet.

We'll walk down to the corner of Collins Street and Swanston Street - the Melbourne Town Hall was a different shape than the one that's there now but in the 1890s it hosted lectures by Mark Twain and Henry Morton Stanley and again in the Shenandoah's day the council had to deliberate on whether it would support the ship. A block up on Swanston and Bourke Street you'd see the Theatre Royal where Barry Sullivan played as well as Joseph Jefferson. The site of the Target Store did have a plaque but that's now gone.

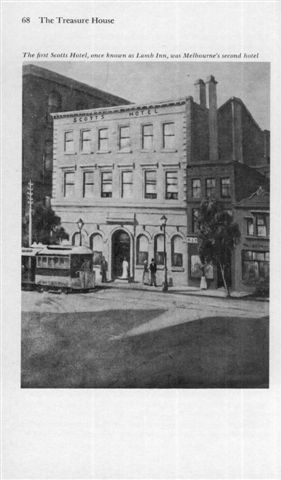

Near the corner of Elizabeth Street and Collins Street you could look down the street and see the Age newspaper building; at the current location of the old stock exchange of the 1960s was the Criterion Hotel owned by Americans who hosted a big Independence Day party every year. Walk a little further, past the offices of J.B. Were, stockbroker (James Benn Were was also one of the circle of men who represented the foreign consuls in Melbourne) and you'd get to Scott's Hotel where the Shenandoah officers stayed. The Royal Insurance Building on this site in the 1960s and 1970s had a placard in the foyer to say that was the site of Scott's Hotel but when it was redeveloped in the 1990s the sign disappeared.

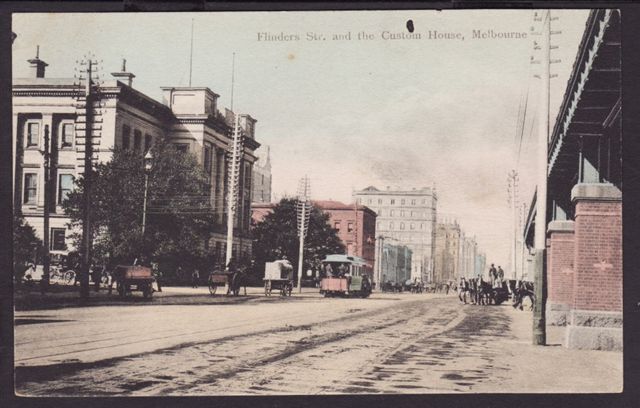

A little bit further and looking down to the Flinders Street railway bridge you'd travel on that to Sandridge (Port Melbourne) across the Yarra River, near that was the Customs House, now the Immigration Museum. The Minister for Customs worked in this building during the Shenandoah's visit, James Francis, who was one of the government's chief ministers due to his dealings with the officers of the ship.

Still walking down Collins Street we get to the Williams Street intersection - a block up at Little Collins Street was the office of the United States consul, William Blanchard (on the corner of Little Collins Street and the laneway, now the new offices of the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria).

Another block down (corner of King Street and Collins Street) you'd see the offices of the company which did all the work on the Shenandoah - Corlies Throckmorton was American and had sympathies for the Confederate raider; look for the opposite corner where the Federal Hotel used to stand, the Federal was where General McArthur stayed in World War 2 - his father, Arthur McArthur, won the Medal of Honor in the Civil War.

A short walk to the end of the city proper brought you to the Spencer Street railway station, now Southern Cross, where the Shenandoah officers took the train via Geelong to Ballarat.

We could continue our travel to Ballarat, or Creswick, or Maldon, or Bendigo, but for now we'll have a drink in one of the many watering holes of 1860s Melbourne and replenish the soggy beer mat. Of those old 1860s public houses, only a handfull remain – Young & Jackson’s Princes Bridge Hotel is on the site though a different name; Macs Hotel in northern Melbourne is one of the few to continually hold a licence with the same name and location.

I can include my photos of Melbourne taken by me alongside photos and illustrations of Melbourne as it looked although there are still several places that I don’t have old photos still to be done.

The Melbourne Baths needs both a photo by me from the digital camera as well as an old illustration and I should be able to locate that from one of the archive places.

There are about sixteen sites of Melbourne associated with either the Civil War or else the visit of the Shenandoah and most of those I already have access to use.

Places so far that I can think of are:

1 Melbourne Baths (Swanston Street where one of the veterans was scalded while taking a bath and later died)

2 Target Centre Bourke Street (site of the old Theatre Royal)

3 Corner of Bourke and Russell Streets (site of the old Alhambra Dance hall)

4 Chancery Lane (site of old office for the US Consul during the Civil War – William Blanchard

5 Toorak Swedish Consulate (site of the old government house where Governor Darling was residing when the Shenandoah arrived)

[This is the new Government House in the Botanical Gardens south of the Yarra, not the one in Toorak]

6 Flinders Street east (site of recruiting station near where the Herald & Weekly Times Building is)

7 Flinders Lane east (site of Photographic studio of Batchelder and O’Neill)

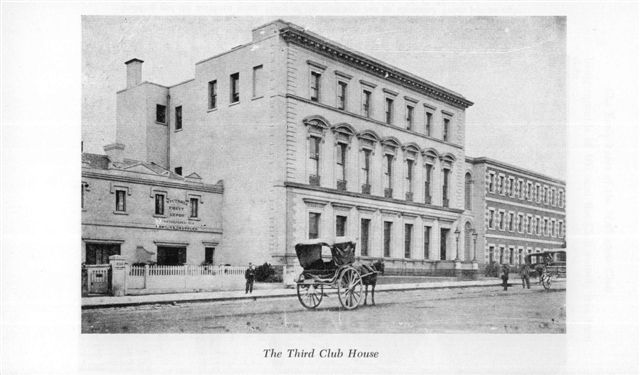

8 Melbourne Club Collins Street. There have been a number of buildings on this site – the Melbourne Club’s current building is the third one so a photograph of the club as it looked in the 1860s is shown below.

9 Town Hall corner of Collins Street & Swanston Street (Henry Morton Stanley and Mark Twain both spoke here). The "new" town hall was opened in 1870 so although it appears as Henry Morton Stanley and Mark Twain would have seen it, for the Shenandoah officers’ visit in 1865, it would have been the previous building.

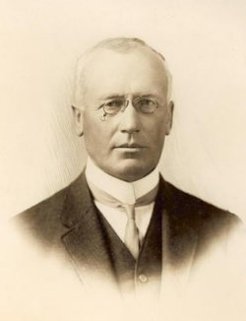

The illustration below is of William Kerr who was town clerk in 1865.

10 440 Collins Street (once the Royal insurance Building and before that Scott’s Hotel)

11 Corner of Collins Street and King Street – 520 Collins Street now the Stock Exchange, was Throckmorton’s store who paid for Shenandoah’s repairs

12 360 Collins Street – was the Criterion Hotel in the 1860s where Fourth of July parties were held

13 North-east corner corner of Queen and Little Bourke Street - Harp and Erin Hotel – where one of the veterans resided

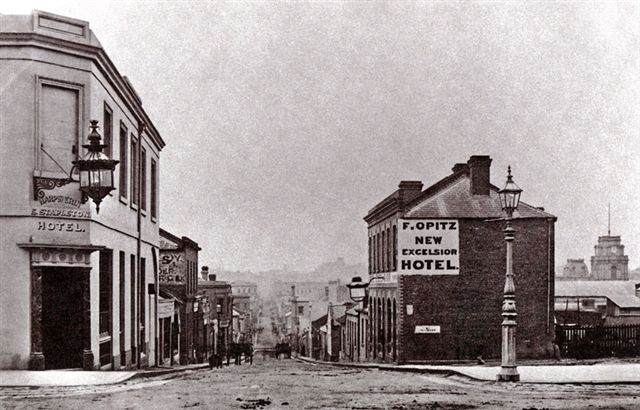

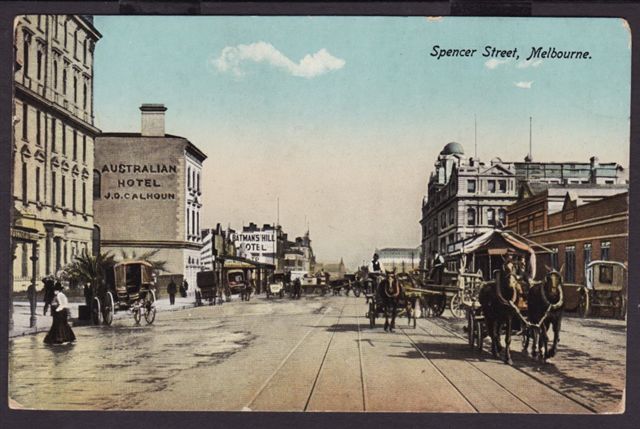

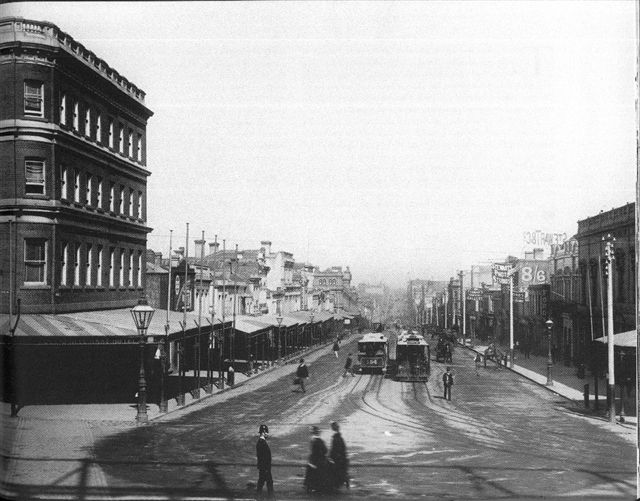

14 454 Flinders Street – between William Street and King Street (north side) was the old SEC Services Buidling, another old veteran resided here – this postcard below shows Flinders Street looking east from Queen Street, or maybe Spencer Street.

A view of the Yarra River from the turning basin

15 Customs House on Flinders Street (Minister for Customs Francis had his offices here)

16 Spencer Street Railway Station (Shenandoah officers left here to go to Ballarat)

17 Shop on Corner of King & Latrobe Streets – I think that one of the officers off the Shenandoah visited the doctor here (to confirm with memoirs)

18 Old Exhibition building (U.S. Consul James Morris Morgan represented the U.S. during the 1885 exhibition)

19 Statue of Sir Redmund Barry outside State Library – possibly was at Shenandoah dinner

20 Parliament House –

The building of Parliament House began in 1856 at the height of the Victorian gold rush. The colonnade facing Spring street was added in in the 1890s. Parliament House was the first home of the Australian Parliament from Federation in 1901 to 1927 when the Federal Parliament moved to Canberra. (from Ebay January 2012)

A premier of the state, William Hill Irvine, had an uncle, John Mitchel, who had been transported to Van Dieman’s Land during the 1848 Irish uprising; he managed to escape with his family, eventually went to the United States where he resided firstly in Knoxville, Tennessee, and later in Richmond, Virginia. All three of his sons served in the Confederate army.

One member of the Mitchel family who continued living in Victoria after the remainder had left and gone to the U.S. was Margaret Mitchel Irvine, who had been John's sister. She married Hill Irvine, also an Irelander, and they had come to Australia as free settlers in the 1870's. Their son, William Hill Irvine Jr., would become premier of the state of Victoria in the early stages of the new century.

Another Irishman in the Civil War with an Australian connection was Thomas Lalor. His brother, Peter, became a well-known identity in the so-called "Eureka" uprising in Ballarat, during the mid 1850's during the Victorian gold-rush and was later a member of the Victorian Parliament. Most of the Lalor family had emigrated to the U.S. between 1830 and 1850 - Tom was known to have been killed in the Civil War. A further two brothers also fought in the war, supposedly on different sides.

The four brothers who went to America were William, Jerome, Tom and Joseph. Tom was supposed to have died in the war but his name does not appear in the most eligible of rosters in "Roll of Honor" which lists all Union dead buried in National cemeteries. A search in the family Intenet sites shows that Tom was killed at the battle of the Wilderness, Virginia, 5 May 1864 (where that information came from I don’t know) but it is confirmed that Thomas Lalor, a private in Company E of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, was missing in action at the Wilderness on the same day.

Further information on those American brothers does not give any more links to the Civil War, John died in Canada and Jerome died on 31 December 1898 and was buried at Independence, Buchanan County, Iowa.

For Peter Lalor, leader of the rebellion at Eureka, it must have been difficult for him to see the Shenandoah sailing up to Melbourne in January 1865, and as he was then a member of the Victorian state parliament, no doubt he was involved with celebrations for the visit of the Confederate ship. I wonder whether he attended the dinner held in their honour at the Melbourne Club?

21 St James Church

22 The Age Newspaper Building, 67 Elizabeth Street (has moved three times after this location – Collins Street, Spencer Street and back to Collins Street). This location was where the newspaper was published at the time of the Shenandoah’s visit. The first view below was Elizabeth Street and followed by the new building at Collins Street.

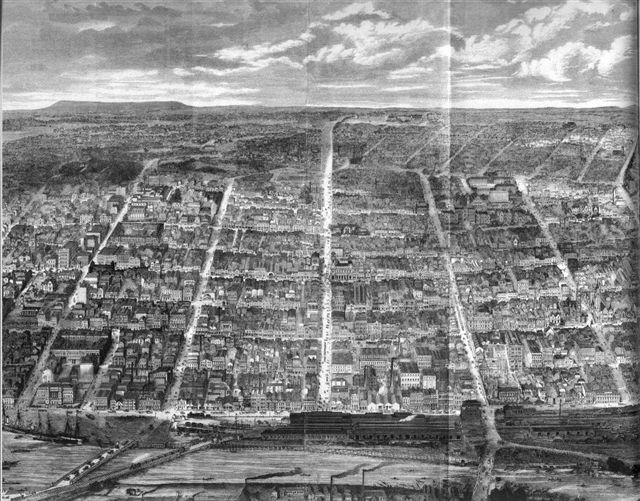

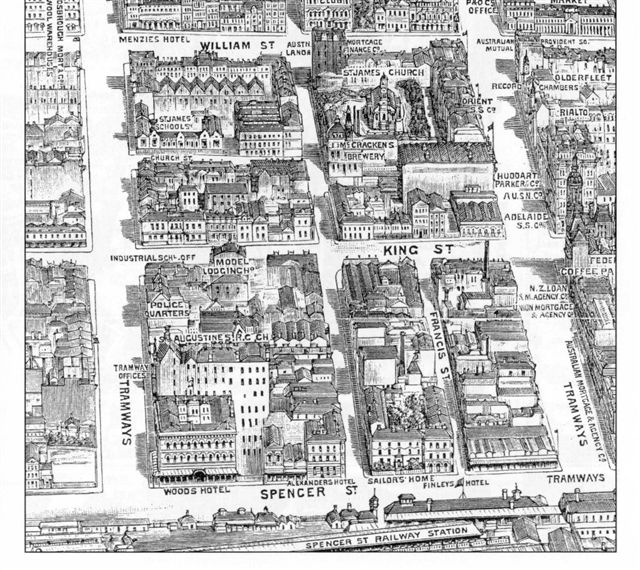

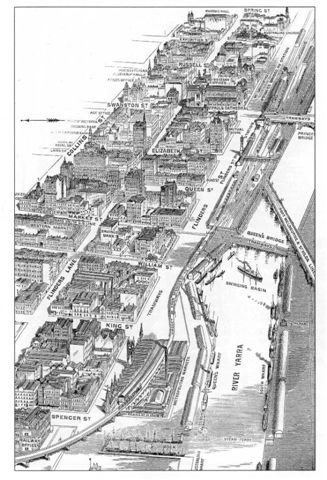

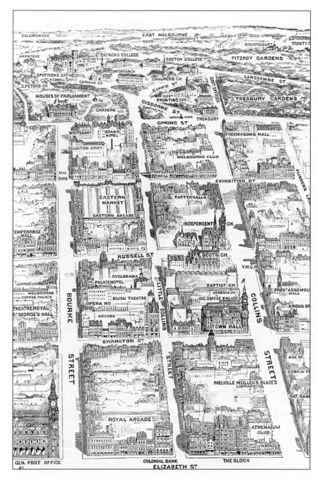

I need to use the illustrations of the Melbourne streets of the 1880s as well as the lay-out of Melbourne in 1887 to get the best angles of where the buildings were – can also sue some of my illustrations and photos of 1860s Melbourne plus illus of Joseph Jefferson

Photos I need to take – Melbourne Baths, maybe another of Sir Redmund Barry, harp & Erin, Flinders Street west, Flinders Street east, Flinders Lane

SHENANDOAH AND THE PEOPLE OF MELBOURNE

Do biographies of the people in Melbourne at the time of the Shenandoah's visit and their relationships to the Civil War

Americans

Freeman Cobb (though he had already left for America)

Thomas W. Stanford

William Blanchard

Joe Jefferson

Peter Lalor

Redmond Barry

Samuel Amess

J.B. Were

Henry Dendy (might have died?)

David Syme

Governor Darling

James G. Francis

Frederick Charles Standish

James I Waddell

Thomas Crompton (from Lanacashire)

Owner of Craigs

Photographer Batchelor

Mine owners in Ballarat who invited Shenandoah crew members

Owner of the dockyards (Langlands)

Phillip Ferguson Jones

Shenandoah crew members

New York Times, 22 September 1861

WILLIAM BLANCHARD, of this city, has been appointed Consul to Melbourne.

(he took over from Maguire who had been appointed by Buchanan?)

WERE, JONATHAN BINNS (1809-1885), stockbroker, was born on 25 April 1809 at Wellington, Somerset, England, the third son of Nicholas Were and his wife Frances, née Binns. In 1829 he joined the firm of Collins & Co., colonial merchants and bankers, of Plymouth. In 1833 he married Sophia Mullet Dunsford (1811-1881), a Quaker. They had twelve children, three of whom died in infancy. In 1882 he married Elizabeth, daughter of Donald Gordon McArthur of Melbourne.

Were emigrated in 1839 and settled in Melbourne. He brought a prefabricated house and merchandise worth about £1500. He traded at first under his own name, then with his brother George and with other partners until 1861, when the title J. B. Were & Son was adopted. Were's were importers, exporters, and agents for shipping, land, cattle, sheep and wool. In 1851 they became brokers and buyers of gold, and in 1853 began to deal in shares.

In February 1841 Were had become an agent for Henry Dendy. Were's subsequent business failure and bankruptcy in 1843 forced Dendy into insolvency; both their interests in the Brighton Estate were acquired eventually by Were's eldest brother Nicholas who lived in England. In 1857, after his second bankruptcy, the firm's share dealings rapidly took precedence over its commerce. In 1859 Were was both chairman and secretary of a regular stock exchange and in 1860 began to operate 'solely as Broker and Agent'. He successfully challenged stock jobbing by campaigning for an exchange on which brokers could not be principals and in 1865 was elected first chairman of 'The Stock Exchange of Melbourne'. He was a leading broker until his death, taking into partnership at various times his sons, Jonathan Henry, Francis Wellington and Arthur Bonville, and his son-in-law Sherbourne Sheppard.

In the 1840s Were was prominent in communal and business activities. He was first president of the Chamber of Commerce, one of three on the standing committee for separation, president of the Bible Society, a member of the Melbourne Hospital Committee, the Immigration Board and other institutions, and a director of many companies. He was the first justice of the peace appointed for Port Phillip, was a leading Church of England layman, and helped to run the 1881 Melbourne Exhibition, after which he was appointed C.M.G. In 1856 he was elected for Brighton to the Legislative Assembly, but his second bankruptcy soon caused his retirement. Contemporaries considered him most notable for the extraordinary number of his consular posts. He was knighted by the kings of Sweden and Denmark.

Were was a strange mixture of worldly ambition and idealism, of breadth of vision and rashness. His life seems to divide naturally into two periods at about 1857. Most of his public service took place in the 1840s and it was then that he lived in some style; 'all was English' at Moorabbin House in Brighton. He died on 6 December 1885.

Portraits are in the possession of J. B. Were & Son, Dr Stuart Were of Balwyn, and the Brighton City Council.

Select Bibliography

T. W. H. Leavitt and W. D. Lilburn (eds), The Jubilee History of Victoria and Melbourne, vol 1 (Melb, 1888); The House of Were 1839-1954 (Melb, 1954); W. Bate, A History of Brighton (Melb, 1962); Argus (Melbourne), 7 Dec 1885. More on the resources

Author: Weston Bate

Print Publication Details: Weston Bate, 'Were, Jonathan Binns (1809 - 1885)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, Melbourne University Press, 1967, pp 589-590.

DENDY, HENRY (1800-1881), special survey proprietor, was born on 24 May 1800 at Abinger, Surrey, England, only son of Samuel Dendy, farmer, of Great Millfields and other property in Sussex and Surrey, and his wife Sarah, née Hampshire, who died when Henry was aged 3. When his father died in 1838, Henry was a brewer at nearby Dorking, which may help to explain why he sold the farms in 1840 and paid £1 an acre for a special survey of 5120 acres (2048 ha) at Port Phillip. He arrived in Melbourne on 5 February 1841 with his wife Sarah, née Weller, whom he had married at Capel, Surrey, on 6 January 1835, and their 5-year-old son Henry.

Dendy's behaviour was extraordinary, especially his attempt to establish a manorial estate in the pastoral colony. Inadvertently, though, he almost made a fortune. If applied to urban land, his order was thought to be worth £100,000. Melbourne's capitalists were agog, and Superintendent La Trobe, alarmed by the unexpected situation, appealed to Governor Gipps, who withdrew from sale land within five miles (8 km) of towns.

Astonished by his potential windfall, Dendy accepted advice from the forceful merchant J. B. Were, who was his agent when the land order was presented to La Trobe on 8 February. Defiantly, they claimed urban land before accepting two miles (3.2 km) of bay frontage at the Melbourne five-mile limit. Their Brighton Estate was surveyed in May 1841.

The ambitious plan, a pace-setter for Melbourne, offered delightful foreshore sites, a township with crescents and an inland village among seventy-eight-acre (33 ha) farms. Dendy built a two-storey 'manor house' and made his seventy-four-acre (32 ha) seafront home, Brighton Park, a show place. In partnership with Were, he played the role of founder, implemented a grant of ten acres (4 ha) to the Church of England and hosted a picnic match between the Brighton and Melbourne cricket clubs. His prosperity seemed assured, although the original manorial dream had been amended. Unable to employ the twenty-nine families and twenty-two single workers he had sponsored under the land regulations, he helped them to settle. They left names like Carpenter, Lindsay, Male and Hampton on Brighton streets; a street was also named after Dendy.

When depression hit the colony in 1843, land sales ceased and bad debts accumulated. Dendy suffered severely but kept afloat until required to honour his guarantee of £1500 on a bank loan to Were. In April 1845 he was declared insolvent, a fate softened by his wife's ownership (as her dowry) of Brighton Park. While Were was sustained by his brother in England, Dendy attempted to recover by brewing at Geelong in 1846-48, but could not keep the Brighton property. When it was sold in 1848, he tried squatting at Christmas Hills in 1849-53 and Upper Moira in 1853-55. The former was miserable, but the latter, near Nathalia, carried 8000 sheep when gold-rush demand for meat was strong. Its sale enabled him to visit England, apparently for several years.

Dendy, the dignified rolling stone, returned to a sheep property near Werribee, then to a flour mill at Eltham, where Sarah died in 1861. He sold the mill in 1867 to go to Gippsland, where he was a director of the Thomson River copper mine. It devoured his capital. Growing old, Henry lived with his son, who drove the engine at the Long Tunnel gold-mine, Walhalla. Pathetically, seeking independence, Dendy asked the friend who had built Brighton Park for materials to do up an old hut in the bush. On 11 February 1881 Dendy died at Walhalla, where he was buried. An epitaph might be the comment of his former servant John Booker: 'a good, honourable, kind master, but no businessman'.

Select Bibliography

W. Bate, A History of Brighton (Melb, 1962); L. A. Schumer, Henry Dendy and his Emigrants (Melb, 1975); Dendy file (Brighton Historical Society, Melbourne).

Author: Weston Bate

Print Publication Details: Weston Bate, 'Dendy, Henry (1800 - 1881)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Supplementary Volume, Melbourne University Press, 2005, pp 99-100.

FRANCIS, JAMES GOODALL (1819-1884), politician, was born on 9 January 1819 in London, son of Charles Francis and his wife Anne, née Smith. On 14 February 1835 he arrived at Hobart Town as a steerage passenger in the Sarah. He became partner in a Campbell Town store in 1840 and later head clerk in the Hobart firm of Boyes & Poynter. About 1850 Duncan McPherson bought the firm and took Francis into partnership; McPherson was consul for the United States and McPherson, Francis & Co. did much business with whaling ships in port. In 1853 Francis moved to Melbourne to open a branch of the firm while McPherson remained in Hobart. The partnership was dissolved in 1860 and next year Francis admitted John McPherson as partner to form Francis & McPherson. Francis was a local director of the Bank of New South Wales until his death; in April 1857 he was elected vice-president and in May president of the Chamber of Commerce. His other interests were legion. He was a director of the Victoria Sugar Co. established in 1857; he had a large part in establishing 'the Australian and Tasmanian Insurance Companies' and in 1857 was a director of the Melbourne Underwriters' Association, known as the Melbourne Marine Insurance Association after 1858. He was interested in gold-mining especially in the late 1850s and in Riverina and Victorian squatting from the late 1870s; in 1884 he held a half-interest in Runnymede, near Casterton, and was buying Monomeith near Cranbourne with P. and J. Bruce. He also invested in coal and Western Australian timber but his favourite hobby was probably the large vineyard he established at Sunbury in 1863.

In 1859-74 Francis represented Richmond in the Victorian Legislative Assembly. On 25 November 1859 he succeeded John King as vice-president of the lands and works board and commissioner of public works in the ministry of William Nicholson. When the cabinet refused to back James Service who threatened to invoke an 1850 Order in Council to make the Legislative Council accept his land bill, Francis resigned with Service on 3 September 1860. This action put him towards the left; so did his mild protectionism. Like other reformist merchants, however, he was separated from radicals by his dislike of agitation and contempt for their administrative capacities. He therefore opposed the part-radical ministry of Richard Heales as incompetent; when it turned wholly radical at the elections of 1861, proposing tariff reform and more administrative action to solve the land question, he despised it the more for its sudden conversion. Like other moneyed reformers he helped to defeat Heales and supported John O'Shanassy's ministry of 1861-63, although except for (Sir) Charles Gavan Duffy it was thoroughly conservative. Francis then became restless when Duffy's Land Act proved a fiasco and helped to defeat the ministry when Duffy proposed to increase pastoral rents fixed by arbitration under his own Act.

Co-operation in 1862 with James McCulloch earned Francis the commissionership of trade and customs in June 1863 in McCulloch's first administration. It was dominated by men of standing but the presence of Heales and three supporters made it easier for Francis to introduce his 1865 tariff. This first move in Victoria towards protection also began a political crisis. The government's victory at the 1864 elections had forced the Legislative Council to accept a liberal land bill, but it determined to counter-attack on the tariff. The government therefore 'tacked' this to the budget, but the council rejected the combined bill in July. Victoria was in uproar. Francis, while far from joining the radical agitators, supported his tariff against his class and saw it pass in March 1866.

The crisis revived in July 1867. A grant to Lady Darling, whose husband Sir Charles had been recalled for alleged partisanship in supporting the ministry in the earlier crisis, was also tacked with a similar result. Francis disliked the unnecessary disruption but extremism prevailed. He supported his colleagues, especially after Colonial Office intervention had forced their resignation in May 1868, but was soon critical of his party's intransigence. This attitude and his business affairs kept him out of the more radical restoration of the ministry after the crisis but he rejoined McCulloch in April 1870 as treasurer in his more conservative third administration. Faced with falling revenue after the 1871 elections Francis proposed even higher duties but, believing 12½ per cent the limit, suggested Victoria's first property tax for the rest. This proposal brought down the government in July and wrecked its party. Duffy's radical ministry successfully increased duties to 20 per cent but fears of another constitutional crisis united members of all persuasions. McCulloch resigned in the Christmas recess and Francis became leader and in June 1872 chief secretary. His pragmatism and moderation symbolized coalition and 'practical legislation'. His democratic style held together a cabinet of able, self-assertive men, some recently bitter opponents, and his majority soon became overwhelming.

Francis did not shun conflict. The 1872 Education Act, which first provided effectively for free, secular and compulsory primary education, belied claims that as an Anglican he had raised the question merely to undermine his Catholic predecessor. The ancient questions of mining on private property, fencing, impounding and land law liberalization were tackled. Acts were passed to reduce mining accidents and implement a long-delayed railway building programme. Constitutional reform was Francis's personal responsibility. In 1873 his proposals, more radical than politic, would have gone far towards one man one vote and one vote one value, liberalize the council and institute double dissolutions in future constitutional crises. These measures were frustrated by the council but Francis acted with determined moderation. Having given the council several opportunities he fought the 1874 elections on his 'Norwegian scheme' to settle disputes between the Houses by joint sittings. His personal majority was undiminished but reservations on the reform bill made its third reading majority fatally narrow. Simultaneously Francis almost died from pleurisy. A large majority urged him to retain office but he refused; the ministry was reconstructed in July under George Kerferd. The chief secretaryship was kept vacant but Francis left parliament in November and went to Britain.

When he returned in 1876 the assembly was polarized between McCulloch's ruling right and the left under Graham Berry. Disgusted, like many liberals, with Berry's violent agitations and McCulloch's intrigues, Francis refused to stand at the 1877 elections which swept Berry into power. The constitutional crisis of 1877-78 changed his mind. Still favouring constitutional reform he feared radical violence and sided with his class and the constitutionalist party. A vacancy was created in West Melbourne but at the poll in February 1878, and again in the ministerial by-election of April, Francis was defeated by political excitement, Catholic opposition and electoral sharp practice. Not until May was he elected for Warrnambool, his seat thenceforth. The crisis was over but in a close-fought campaign on the nature of council reform his experience greatly helped his party. He was minister without portfolio in Service's constitutionalist cabinet from March to August 1880 but health limited his activities; when Service left for England in March 1881 Francis would not seek the leadership and instead was the recognized adviser of the new leader, Robert Murray-Smith. He took over as leader in April 1882 after Smith became agent-general.

Meanwhile Berry had passed a reform Act but his government had promptly fallen and a scratch ministry was assembled by Sir Bryan O'Loghlen in July 1881. Francis's party, unable to rule alone, gave O'Loghlen a majority but with increasing reluctance, for Francis still mistrusted Berry. Worsening health reduced his influence and he began to doubt the ministry's financial competence; when the disappointing results of a major loan took O'Loghlen to the hustings in February 1883 Francis abandoned him. He stood down in favour of Service but when neither party won a majority accepted a coalition with Berry. His health collapsed and he died on 25 January 1884 at Queenscliff. He was survived by his wife Mary Grant, née Ogilvie, whom he had married at Hobart; they had eight sons and seven daughters. His estate was valued at more then £178,000.

Francis was no political giant. An effective administrator, he lacked the necessary touch of political ferocity and skill in manoeuvre; he also admitted that he was a wretched speaker. With the giants briefly removed in 1872-74, his straightforward, level-headed independence and modesty were what the times required. If he could not inspire awe, fear or passion, he had a rare capacity for winning confidence and affection. He never sought the trappings of power and three times refused a knighthood as inappropriate to colonial society. Had his health allowed, his qualities might have brought him an enviable and continuing political success.

Select Bibliography

A. S. Kenyon, ‘The James Hamilton letters’, Victorian Historical Magazine, 15 (1933-35); Argus (Melbourne), 25 Aug 1859, 1 Aug 1861, 26 Jan 1884; Leader (Melbourne), 25 July 1863; Illustrated Australian News, 20 Feb 1884; F. K. Crowley, Aspects of the Constitutional Conflicts … Victorian Legislature, 1864-1868 (M.A. thesis, University of Melbourne, 1947); J. E. Parnaby, The Economic and Political Development of Victoria, 1877-1881 (Ph.D. thesis, University of Melbourne, 1951); G. R. Bartlett, Political Organization and Society in Victoria 1864-1883 (Ph.D. thesis, Australian National University, 1964).

Author: Geoffrey Bartlett

Print Publication Details: Geoffrey Bartlett, 'Francis, James Goodall (1819 - 1884)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, Melbourne University Press, 1972, pp 211-

LALOR, PETER (1827-1889), Eureka stockade leader and politician, was born on 5 February 1827 in the parish of Raheen, Queen's County, Ireland, son of Patrick Lalor (pronounced Lawler) and his wife Ann, née Dillon. The family was descended from the O'Lalours, one of the Seven Septs of Leix who had fought against the English invasion of Ireland in the sixteenth century. The Lalors had leased the 700 acres (283 ha) of Tenakill since 1767 and remained fairly prosperous until the great famine of 1845. They were supporters of Ireland's freedom from British rule and of the rights of the Irish peasantry. In 1831 Patrick Lalor had led the resistance of the Leix peasants against the forcible collection of tithes for the established church and in 1832-35 represented Queen's County in the House of Commons where he was an ardent advocate for the repeal of the Act of Union. In 1853 he wrote: 'I have been for upwards of forty years struggling without ceasing in the cause of the people'.

The eldest of Patrick's eleven sons, James Fintan, became a leader of the Irish Confederation and the 'Young Ireland' movement of 1848. According to (Sir) Charles Gavan Duffy, he was 'the most original and intense … of all the men who have preached revolutionary politics in Ireland'. In the Nation he expounded his belief in 'Ireland her own, from the sod to the sky'. He became co-editor of the Irish Felon in 1848 but was in Newgate prison during the uprising. On his release, he plunged into a new unsuccessful revolutionary conspiracy. He died in December 1849. Fintan had urged his brother Richard in 1848 to form Confederate clubs and engage a blacksmith to make pikes for the peasants. Fintan's letters record only the suggestion that Peter should join the Felon club and that Richard should bring him to Dublin to take part in the rising.

Peter's early years were overshadowed by these dramatic events and by the famine but no evidence shows that he was actively involved. Later he commented that 'from what he had seen of the mode of conducting politics in [Ireland] he had … no inclination to mix himself up with them'. Educated at Carlow College and in Dublin, he became a civil engineer. The years after the famine saw a great emigration from Ireland. Three of the Lalor brothers went to America while Peter and Richard migrated to Victoria attracted by the gold discoveries. They arrived at Melbourne in October 1852 and Peter found work on the construction of the Melbourne-Geelong railway; he and Richard also became partners with another Irishman as wine, spirits and provision merchants in Melbourne. In 1853 Peter left for the Ovens diggings. Early in 1854 he moved to Ballarat. Richard did not accompany him to the diggings and soon returned to Ireland where he became a member of parliament for Leix in 1880-92 and was an ardent Home Ruler and supporter of Parnell. Peter apparently saw himself as much merchant as digger, since he bought from the partnership over £800 worth of tobacco, spirits and other supplies; however, his departure for the goldfields ended his career as a city merchant.

At Ballarat Lalor staked a claim on the Eureka lead, where many Irish diggers were concentrated, although his own 'mate' was Duncan Gillies, a Scot. He was reported to be among the shrinking minority of Ballarat diggers who were having 'fair luck' on their claims; he was involved, although not prominently, in the agitations over the miners' licence and 'digger-hunting'. Later Lalor wrote, perhaps thinking of the wrongs of Ireland, 'the people were dissatisfied with the laws, because they excluded them from the possession of the land, from being represented in the Legislative Council, and imposed on them an odious poll-tax' (licence fee) which an arbitrary officialdom sought to collect from diggers.

The Ballarat Reform League arose from the agitation against the imprisonment of three diggers charged with the burning of Bentley's Hotel. The league's programme reflected the radical beliefs of its leaders: it was overtly Chartist in its demands and, some said, covertly republican. Lalor was a member of the committee, although he must have had reservations about parts of its programme. On 29 November 1854 the league called its first mass meeting to hear the report of its deputation to the governor. Sir Charles Hotham had promised an inquiry into the diggers' grievances but refused to accede to the diggers' 'demand' for the release of their mates. The mood of the 12,000 diggers who gathered on Bakery Hill for the first time under their Southern Cross flag was for physical resistance. Resolutions were carried calling on the diggers to burn their licences and pledging the protection of the 'united people' for any digger arrested for non-possession of a licence. Lalor's first public appearance was at this meeting: he moved for a further league meeting on 3 December in order to elect a central committee.

On 30 November the troops had undertaken a 'digger hunt' on Bakery Hill. The news of the resulting clash spread rapidly through the diggings to the Eureka, where Lalor was working in his shaft, 140 ft (43 m) below ground, with Timothy Hayes, chairman of the league, at the windlass above. Diggers rushed to the scene and, as the troops withdrew with their prisoners, occupied the hill where the flag was again raised. The diggers dispersed to gather strength and resolved to reassemble at 4 p.m. None of the regular spokesmen was then present and Lalor 'mounted the stump and proclaimed "Liberty".' He called on the men to arm themselves and to organize for self-defence. Some hundreds were enrolled and Lalor, according to Raffaello Carboni, 'knelt down, the head uncovered, and with the right hand pointing to the standard, exclaimed in a firm measured tone: "We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other to defend our rights and liberties". A universal well-rounded Amen, was the determined reply'. That night Lalor wrote to his fiancée, Alicia Dunne, a school-teacher in Geelong: 'the diggers … in self-defence, have taken up arms and are resolved to use them … I am one amongst them. You must not be unhappy on this account. I would be unworthy of being called a man, I would be unworthy of myself, and, above all, I would be unworthy of you and of your love, were I base enough to desert my companions in danger'.

Next morning some 1500 diggers assembled on Bakery Hill and marched behind their flag to the Eureka. The leaders met and appointed Lalor commander. In response he said: 'I expected someone who is really well known to come forward and direct our movement. However, if you appoint me your commander-in-chief, I shall not shrink. I tell you, gentlemen, if once I pledge my hand to the diggers, I will neither defile it with treachery, nor render it contemptible with cowardice'.

In the next two days both sides continued their preparations. The diggers threw up a barricade of which Lalor wrote, 'it was nothing more than an enclosure to keep our own men together, and was never erected with an eye to military defence'; yet it closely resembled the fortified circular encampments planned by Fintan Lalor in 1848. Behind it, the men drilled and blacksmiths manufactured pikes. Lalor claimed no military expertise; he appointed a young American to look after the military side while he organized picketing and the procurement of arms, ammunition and other supplies. The government camp organized for action and infiltrated the stockade with spies.

Lalor did not expect an immediate attack and did not plan to confine defence to the stockade. By midnight on Saturday only about 120 men were left in the stockade, most of them Irish. Some hundreds had left to spend the night in their tents. At about 3 a.m., Sunday, 3 December, the troops and police attacked. They quickly stormed the flimsy stockade and its defences, killing thirty or more diggers and taking over a hundred prisoners. True to his pledge Lalor had stood his ground but was hit in the left arm and collapsed. He was hidden under logs and escaped the bayonets of the attackers. He was smuggled from the battlefield and eventually reached the home of Father Smyth, where his arm was amputated at the shoulder by a party of doctors. Legend has Lalor recovering consciousness during the operation and, seeing one doctor with signs of faintness, saying 'Courage! Courage! Take it off!'

Hotham offered a reward of £200 for information leading to the apprehension of a 'person of the name of Lawlor … height 5 ft 11 ins [180 cm], age 35, hair dark brown, whiskers dark brown and shaved under the chin, no moustache, long face, rather good looking and … a well made man' who at Ballarat 'did … use certain TREASONABLE AND SEDITIOUS LANGUAGE, and incite Men to take up Arms, with a view to make war against Our Sovereign Lady the QUEEN'. There were no takers: public sympathy was overwhelmingly with the diggers. Lalor remained concealed in Ballarat for several weeks; from there he was taken by dray to Geelong, where he was cared for by Alicia Dunne and married her on 10 July 1855 at St Mary's Church.

Public subscriptions for the disabled Lalor raised enough money for him to buy '160 acres [65 ha] of very good land within 10 miles [16 km] of Ballaarat'; he emerged from hiding to bid for the land and was not arrested. In March the reward had been revoked, and in April the thirteen diggers charged with treason were acquitted. The colonists generally shared Lalor's judgment of the stockade: 'neither anarchy, bloodshed, nor plunder, were the objects of those engaged … Stern necessity alone forced us to do it'. One eye-witness reports Lalor as saying that his object as leader was 'independence'; if this were so, it would seem that the independence he wanted was from arbitrary rule, from encroachments by the Crown on 'British Liberty', and that granted by access to the land, rather than the 'independence' of a republican democracy.

With the adoption of the recommendation of the commissioners appointed by Hotham to inquire into the condition of the goldfields that the Legislative Council be enlarged to include elected representatives of the goldfields, Lalor was one of two diggers' leaders returned unopposed in November 1855 to represent Ballarat. He told his electors: 'I am in favour of such a system of law reform as will enable the poor man to obtain equal justice with the rich'. When the first parliament was elected under the new Constitution in 1856 Lalor was returned unopposed to the Legislative Assembly for North Grenville, a Ballarat seat. He was appointed an inspector of railways at a salary of £600, but was soon debarred from this post when legislation was passed prohibiting civil servants from sitting in parliament.

In the assembly Lalor spoke out for the interests of the diggers: he successfully advocated compensation for the victims of Eureka, and unsuccessfully the right of miners to enter private property in search of gold; in vain he opposed the appropriation of funds for a memorial to Hotham, saying, 'There was sufficient monument already existing in the graves of the thirty individuals slain at Ballarat'. Yet he aroused hostility among his digger constituents by supporting plural voting on a property franchise and a six-months' residency qualification for the franchise, and land legislation which radicals held to favour the squatters. In defence he said that he would never consent to deprive a freeholder of his right to vote in virtue of his freehold, and that the danger inherent in conferring the franchise on 'an unsettled population' should be balanced 'by infusing into the people a conservative element by attaching them to the land'. He denied that he was a democrat if that meant 'Chartism, Communism, or Republicanism', but asserted that 'if democracy means opposition to a tyrannical press, a tyrannical people or a tyrannical government, then I have ever been, I am still, and will ever remain, a democrat'. The diggers were not convinced, and Lalor wisely stood for South Grant in 1859. He was elected and became chairman of committees at a salary of £800.

Lalor's stance in parliament appeared puzzlingly inconsistent. He was an early advocate of protection of local industry, believing that it would provide work for men no longer able to make a living on the goldfields, but he also supported assisted immigration. Although a devout Roman Catholic, he opposed state aid to religion and supported a national education system provided that provision was made for religious teaching. He supported the 1860 and 1862 Land Acts providing for selection from the squatters' runs, but urged sale by auction of both freehold agricultural land and grazing leases, declaring that the creation of 'a middle class of landed proprietors' able to employ labourers at reasonable wages, was preferable to opening the land in small lots to men without capital. He supported reform of the Legislative Council but opposed payment to members. When the McCulloch government came into conflict with the council over the protectionist tariff and later the 'Darling grant', Lalor urged caution and abstained from voting on several of the government's vital measures, holding them to be unconstitutional.

Lalor's pursuit of his own judgment won him no friends in parliament, yet as a good local member with a strong personal following he topped the poll for South Grant in 1868. The ministry repaid his 'unsoundness' by refusing to reappoint him as chairman of committees. In the next three years Lalor virtually abandoned parliament for private business, attending only 31 of 174 divisions. He operated as a land and mining agent and was director of several mining companies, the most important being the New North Clunes. He was also chairman at a substantial salary of the Clunes Water Commission. On his initiative legislation was passed enabling the commission to borrow money for the construction of a water supply system for Clunes. The money was raised by the New North Clunes Mining Co. In 1873 the government bought the commission for £65,000, thus enabling New North Clunes to declare what the Ballarat Star described as the largest dividend ever paid by a mining company—£30 a share. It was also alleged that Lalor employed blacklegs to enforce a wage cut in one of his mines. Lalor was narrowly squeezed out of third place in the 1871 election by Jonas Levien whom he angrily described as 'a little jew boy' and against whom he pursued a vendetta.

The 1874 election was fought on the reform of the Legislative Council. Lalor was by now convinced that domination of the council by squatters made reform necessary, and that its powers should be limited to those enjoyed by the House of Lords. He was elected third member for South Grant. When (Sir) Graham Berry formed his first government in 1875, Lalor became commissioner for customs. The government was defeated after a few months but Berry was refused a dissolution by the governor and led his followers in a stonewalling campaign to disrupt the conduct of business. Lalor supported Berry's tactics wholeheartedly.

In the 1877 election Lalor again backed all Berry's policies, including payment of members. He won a landslide victory, and Lalor became postmaster-general and as commissioner for customs negotiated in vain with Sir Henry Parkes to remove the border duties between Victoria and New South Wales. When the council refused to accept the payment of members, Berry retaliated by sacking the colony's senior public servants. Melbourne Punch laid this 'Black Wednesday' at the door of Lalor who had been outspoken in denouncing the 'arrogant power' of the council. However, Lalor twice embarrassed the government and asserted his independence by voting against measures which Berry believed significant.

The Berry government was defeated in 1880 but Lalor topped the poll for South Grant as a Berryite. In a later election that year Berry won again and moved for the appointment of Lalor as Speaker. Although denounced by Thomas Bent as a 'rebel against the British crown' and as having been 'drunk on the floor of this House', Lalor was appointed unopposed. 'The first duty of a Speaker', he said, 'is to be a tyrant. Remove him if you like, but while he is in the chair obey him. The Speaker is the embodiment of the corporate honour of the House. He is above party. He is the greatest representative of the people'. Despite conservative fears that Lalor would lean towards his political friends he maintained the strength, dignity and impartiality of the chair, and was reappointed by successive parliaments until diabetes weakened his physique and impaired his judgment. The death of his only daughter and in May 1887 of his wife greatly affected him, and he resigned as Speaker in September.

The premier, Duncan Gillies, introduced a bill to grant Lalor £4000 to free him of financial worries in his last months. Despite party opposition in the assembly the bill was passed and later carried unanimously in the council. Earlier Lalor had refused the offer of a knighthood. In a bid to regain his health he took leave from parliament, but remained a member at the express wish of his constituents, and went by sea to San Francisco. On his return he became bedridden in the home of his only son, Joseph, where he died on 9 February 1889. Besides the requiem in Melbourne, flags were flown at half-mast and a special memorial service was held at Ballarat.

On entry into parliament Lalor had been described by the Argus as 'a bluff, straight forward gentleman who blurts out plain truths in a homely matter-of-fact style'. Certainly as diggers' leader and as parliamentarian he fought with courage, determination and often passion for the truth as he saw it. His loyalties were to principles rather than to individuals. The inconsistencies of his political stance can perhaps best be explained by the principles he consistently upheld: a well-ordered society based on a broad and prosperous land-holding class, governed by free men in the liberal institutions embodied in British constitutional procedures. Only when a class claimed exclusive and overbearing power and sought to impose its will arbitrarily was Lalor's anger aroused and turned him, however reluctantly, to action. Once committed to a course he did not waver from it. Neither a profound thinker nor a skilful politician, Lalor was a good fighter and a man of rectitude who came finally to earn the respect even of those whom he had most vehemently opposed on grounds of principle.

Select Bibliography

W. B. Withers, The History of Ballarat (Ballarat, 1887); L. Fogarty (ed), James Fintan Lalor (Dublin, 1947); T. J. Kiernan, The Irish Exiles in Australia (Melb, 1954); Historical Studies, Eureka Supplement (Melb, 1965); C. Turnbull, 'Eureka', in C. Turnbull, Australian Lives: Charles Whitehead, James Stephens, Peter Lalor, George Francis Train, Francis Adams, Paddy Hannan (Melb, 1965), pp 42-71; Parliamentary Debates (Victoria) 1856-87; Australasian, 19, 26 June 1880, 17, 24 Sept 1887, 16 Feb 1889; Freeman's Journal (Sydney), 16 Feb 1889; J. Parnaby, The Economic and Political Development of Victoria, 1877-1881 (Ph.D. thesis, University of Melbourne, 1951); G. Robinson, The Political Activities of Peter Lalor (B.A. Hons thesis, University of Melbourne, 1960); Lalor family papers (National Library of Ireland). More on the resources

Author: Ian Turner

Print Publication Details: Ian Turner, 'Lalor, Peter (1827 - 1889)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, Melbourne University Press, 1974, pp 50-54.

AMESS, SAMUEL (1826-1898), building contractor, was born at Newburgh, Fife, Scotland, son of Samuel Amess, miller, and his wife Elizabeth, née Fotheringham. On leaving private school he was apprenticed to a stonemason. In 1852 he sailed to Victoria and after some success at the goldfields was able to start as a building contractor early in 1853 in Melbourne. He bought land in William Street and the house he built there remained his home until his death. Amess built the Treasury, the 'Old Exchange', the Customs House, the Kew Lunatic Asylum (a contract of about £120,000), the Government Printing Office and many country railway stations. He was the contractor for the west facade of Parliament House but in 1883 was involved in a dispute over the facing stone and lost the contract. In the 1870s he was regarded as Melbourne's foremost building contractor and in 1873 was the first president of the Builders and Contractors Association.

In 1864 Amess was elected to the Melbourne City Council. As mayor in 1869-70 he organized and paid for the ceremonies and festivities associated with the opening of the new town hall in August 1870. Amess commissioned Henry Kendall and Charles Horsley to write a cantata for the concert which 4500 people attended, and he gave a magnificent fancy dress ball at which 3000 guests dined on boars' heads, sucking pigs, jellies and champagne. Amess described his 'sparing the corporable funds' as 'a simple act of duty … The contrary course would have left room for cavilling and question, alike humiliating and vexatious to the members of the City Council'.

Amess was an alderman and a justice of the peace and though he grew less active in business he remained a trusted municipal figure. He represented the city council on the Metropolitan Board of Works and the Harbor and Tramway Trusts. He was a member of the West Melbourne Presbyterian Church and Literary Institute. He also spent his retirement in improving his property on Churchill Island in Westernport Bay which he stocked with horses, quail, pheasants, rabbits and Highland cattle. Aged 71 he died on 2 July 1898 after a short illness aggravated by his insistence on attending to his public duties. He was survived by three of his six sons (educated at Melbourne Grammar School) and two daughters. His wife Jane, daughter of Ralph Straughan, whom he had married in 1849, predeceased him.

Select Bibliography

H. M. Humphreys (ed), Men of the Time in Australia: Victorian Series (Melb, 1878); A. Sutherland et al, Victoria and its Metropolis, vol 2 (Melb, 1888); Argus (Melbourne), 10, 12 Aug 1870, 4 July 1898; Leader (Melbourne), 9 July 1898; Age (Melbourne), 2 Aug 1946. More on the resources

Author: J. Ann Hone

Print Publication Details: J. Ann Hone, 'Amess, Samuel (1826 - 1898)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 3, Melbourne University Press, 1969, p. 29.

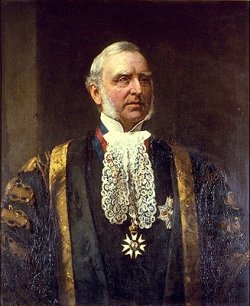

BARRY, Sir REDMOND (1813-1880), judge, was born on 7 June 1813 at Ballyclough, County Cork, Ireland, the third son of Major-General Henry Green Barry and his wife Phoebe, née Drought. Brought up an Anglican, he was educated first at 'Old Curtain's' private academy on the shores of Cork Harbour. At 12 he was sent to a boarding school at Bexley, Kent, which specialized in preparing boys for the army. In 1829 he returned to Ireland hopeful of a commission but, despite many efforts over ten years, none was to be had. He spent the decade profitably, however, for he graduated from Trinity College, Dublin (B.A., 1837), was admitted to the Irish Bar in 1838, and attended at Lincoln's Inn, from which he received a testimonium in August 1838.

While securing these formal qualifications, his other activities showed all his most engaging characteristics. He read widely, attended lectures on both humane subjects and the natural sciences, listened to debates in the Commons, took much vigorous exercise riding, tramping and swimming, and engaged in a warm and lively social life seasoned with many acts of kindness to his friends and family. He became an intimate friend at this time of the brilliant Isaac Butt, founder of the Irish Home Rule movement and defender of William Smith O'Brien. In short he was ceaselessly active both mentally and physically, and so he remained till his last days. But in these ten years he earned virtually no income, and the overcrowded Irish Bar offered no prospects; when his father died in May 1838 emigration became almost a necessity.

After a rapid tour of the Continent he sailed from London in the Calcutta on 27 April 1839 and arrived in Sydney on 1 September. For part of the voyage he was confined to his cabin by the captain because of an unconcealed love affair with a married woman passenger. The matter became known to Bishop William Grant Broughton and other influential people, and did not help his reputation or prospects of employment in Sydney. He was admitted to the Bar there on 19 October. After seeking positions in New South Wales and writing to inquire about vacancies in Van Diemen's Land, he sailed for the new Port Phillip settlement in the Parkfield on 30 October but did not land there until 13 November, so foul was the weather. From that day Melbourne was his home. No sense of exile enters his large private correspondence to England and Ireland. Though his values were wholly those of the cultivated European, he sought to plant these values in his new land and had nothing in common with many of his fellow colonists who saw the settlement chiefly as a means to the fortune which would enable them to retire home in comfort to the British Isles.

The few pounds he had brought from Ireland were almost spent by the time he landed in Melbourne and he took as both lodging and chambers one back room in Mrs Hoosan's cottage in Collins Street. Since no judge of the Supreme Court was then resident in Melbourne he engaged busily in the inferior courts. On 12 April 1841, the first day of the first sittings of the Supreme Court in Melbourne, Barry was admitted to practice by its first judge, the vituperative and eccentric John Walpole Willis. In the two years that Willis presided Barry showed another of the qualities by which he was to be remembered — his invincible politeness and unfailing, if elaborate and old-fashioned, courtesy. His diaries show that the gross provocation of Willis from the bench often reduced the young barrister to a state of almost unendurable tension; yet his decorous demeanour in court was never seen to be ruffled.

In the early years of Melbourne Barry became unofficial standing counsel for the Aboriginals. He laboured as hard and as earnestly upon their cases, often capital matters, as he did upon his other briefs, though he rarely, if ever, received a fee for such services. His interest in the Aboriginals was general and lasted all his life. Though he accomplished for them little of practical value, his open-minded and unprejudiced approach was in advance of that of many even of the most liberal of his contemporaries.

On 2 January 1843 Governor Sir George Gipps sealed Barry's appointment to a minor judicial post, commissioner of the Court of Requests. This was a small debts court and his salary was £100, later increased to £250, plus a proportion of the court fees. The court sat only for the first few days of each month, and Barry therefore retained and developed his private practice. At the same time he was watching the possibility of securing a more important official post and applied unsuccessfully for a commissionership of crown lands.

In 1851, when the Port Phillip District was separated from New South Wales as the colony of Victoria, Barry was appointed its first solicitor-general, a position which he held briefly, for he was elevated to the new bench of the Supreme Court of Victoria in January 1852. He was the first puisne judge of that court and, after the appointment of (Sir) Edward Williams as a second puisne judge in July 1852, Barry held the appointment of senior puisne judge until his death.

During his whole residence in Melbourne Barry was prominent or foremost in every phase of social, cultural and philanthropic activity. To list all the causes or organizations whose interests he promoted would be almost impossible; as examples, he was a founder of the Melbourne Mechanics' Institute (now the Athenaeum), a prominent member of the Separation movement, thrice president of the Melbourne Club, active in the Melbourne Hospital, the Philharmonic Society, the Philosophical Institute, the Royal Society of Victoria — even the Polo Club. He also held a commission in the Victorian Volunteers, the local militia. It is curious, and is perhaps attributable to his friendship with many prominent squatters, that he seems to have played no active part in the anti-transportation movement, though his opinions were distinctly against sending convicts to Victoria. His concern for the diffusion of learning was such that he allowed members of the public to come at night to read books and journals in his house, before there was a public library. In 1841 he was challenged to a duel by Peter Snodgrass, arising out of a letter sent by Barry to a friend, in which he referred to Snodgrass in derogatory terms. The farcical elements of this 'affair of honour' reached their climax when Snodgrass fired prematurely in nervous haste, while Barry magnanimously and ceremoniously fired his pistol into the air.

His private benevolence was liberal, though discreetly bestowed. Irish famine relief, the building of new colonial churches both Protestant and Catholic, the needs of less fortunate relations in Ireland and the alleviation of personal distress in Melbourne all made inroads upon a fortune which, though never great, he did not seek to augment by speculation. Public labour left little time for private aggrandizement; at various periods of his life he trod uncomfortably near the edge of real financial difficulty and died a poor man.

Though already a celebrity when he ascended the bench, he had not even begun his greatest and most enduring works. He was (despite beliefs that the credit belongs largely to Hugh Childers) the indubitable prime founder of the University of Melbourne, of which he was first chancellor (1853), a position he held till his death. He was equally the father of the Melbourne Public Library (now the State Library of Victoria) and its then associated Art Gallery. Over the library trustees too he presided until his death. In both spheres his achievement was great, for the university was able to attract outstanding men as its first professors and well within Barry's lifetime its degrees grew to command world-wide respect. In the same period the library became recognized as one of the great collections of the world, administered upon the most liberal principles. Any detailed criticism of the precise significance of Barry's role in the development of these institutions must recognize that the greatest help came from his drive, energy and influence, his ceaseless care and toil for them, rather than from any more refined or subtle intellectual powers. He was as capable at dusting the books or acting temporarily as porter as at chairing the trustees' meetings at the library. At the university he would pace out the dimensions of some new building on the muddy ground before going in to preside as chancellor. He was criticized in both capacities for being autocratic. In rebuttal it could be argued that if he had not made the decisions and done the work nothing would have been accomplished, for often he was the sole person to attend meetings of which due notice had been given.

As a judge he was hard-working, competent and conservative. He undertook more than his fair share of the cases, worked very long hours and endured the arduous travel by coach, train or horseback required by the circuit courts. Moreover, because he lived nearer to the city than any of the other judges, his leisure was frequently interrupted by urgent applications at his house for legal processes. He gave much thought to matters concerned with the general administration of the law, to the quality of the Supreme Court Library, to the design of the new and splendid court buildings in William Street, though he did not live to sit there.

In 1864 he was involved in a dispute with the attorney-general, George Higinbotham, over the relationship between the judges and the Crown. Barry wrote direct to the governor, Sir Charles Darling, informing him that he proposed to take a short leave in Sydney. Higinbotham insisted that an 'officer of his Department' had no right to take such a step. To admit himself merely 'an officer' of the department of such a democratic attorney-general as Higinbotham was anathema to Barry, and the dispute was acrimonious.

In criminal cases Barry had a reputation for harshness, though it was a harsh period and he was in tune with his times. The florid and slightly sanctimonious speeches with which he frequently seasoned his sentences cannot have made him loved, and certainly he valued the purely retributive elements of the law. Yet he supported the Discharged Prisoners' Aid Society and stressed the importance of the rehabilitation of a criminal who had paid his debt to society. He thought of Victoria as a frontier area where the law was not yet sufficiently respected. In sentencing Henry Garrett to ten years labour on the roads for robbery in company in 1855, he said: 'The sentences of the Court may be thought harsh, but those sentences will be mitigated as the country becomes more settled and composed'. He presided over the trials of most of the Eureka rebels in 1855, including that of Raffaello Carboni. No charge of bias or harshness can be urged against him here, and all the accused were acquitted. In the cases of the convicts accused of the murder of John Price, inspector-general of penal establishments in 1857, he conducted the several trials with a rigor and severity out of keeping with the best judicial attitude, and is perhaps most open to criticism for refusing to assign counsel to defend the accused. Probably his most famous trial was that of Ned Kelly in 1880. Though the Kelly legend continues to excite attention, no substantial criticism of Barry's conduct of that trial can be sustained.

When the chief justice, Sir William à Beckett, resigned in 1857 Barry very reasonably expected to succeed him. The post went instead to (Sir) William Stawell, the attorney-general, after a series of political manoeuvres hardly in accordance with the highest traditions for judicial appointments. Their letters show that relations between Stawell and Barry remained unhappy, and the disappointment was one that Barry never forgot.

On 18 August 1846 Barry made the acquaintance of Mrs Louisa Barrow, a woman of small education and lower social position than his. Though they never married, the relationship between them remained affectionate, tender and devoted in the extreme until the end of Barry's life. She bore him four children, Nicholas, Eliza, George and Fred (b.1847, 1850, 1856, 1859 respectively), all of whom took Barry's name. Parents and children frequently appeared together on public occasions such as theatre performances. The relationship earned him occasional criticism, especially from Charles Perry, the Anglican bishop, yet it was not a cause of his failure to be appointed chief justice. Mrs Barrow farmed a property at Syndal to the east of Melbourne and Barry, in his spare time, cultivated another small property near by — his 'Sabine farm'. Both fronted what is now High Street Road. His city residence, for most of his judgeship, was in Carlton Gardens near the present Exhibition Building. He lived and entertained here on a scale of some splendour. For Mrs Barrow he built a city house at 82 Brunswick Street, Fitzroy.

Apart from shorter sea voyages to other colonies and New Zealand he made two visits abroad, one in 1862 to England and Europe, and the other in 1877-78 to America, England and Europe. Both tours were connected with major exhibitions to which he was commissioner for the Victorian exhibit. However, he regarded the voyages very little as an opportunity for recreation but devoted his time to extremely hard work on behalf of the University of Melbourne, the Public Library and the Art Gallery. He was created K.B. in 1860 and K.C.M.G. in 1877. The inscription on the base of his statue in Swanston Street, outside the State Library, omits to record the latter honour. On various occasions he was acting chief justice, and once briefly administrator of the government of Victoria.

After a very short illness he died in East Melbourne on 23 November 1880, only twelve days after the execution of Ned Kelly. He was buried in the Melbourne general cemetery; although the gravestone does not record it, Mrs Barrow was buried beside him upon her death some years later.

In affairs of the mind Barry was a classicist and a traditionalist rather than an innovator, a man of immense energy and conviction rather than of subtlety. He tended to be a little behind rather than abreast of the great new ideas of his time, as for example in controversies over evolution. An unsuccessful move to depose him as chancellor was made by more 'modern-minded' elements during his absence in 1877-78, though the attempt was also partly motivated by personal spite and in the knowledge that Barry had freely offered his resignation before he embarked. He remained an Anglican, though a formal one without any trace of 'enthusiasm'. He was completely tolerant in religious matters and abhorred the sectarian bitterness of Victorian public life. In his later days it was said that he became vain and pompous, yet perhaps no other Australian city has had so notable a benefactor, and the tribute of his contemporary Garryowen is well merited: 'He was the most remarkable personage in the annals of Port Phillip, for he threw in his lot with the destiny of the Province when it was a weak struggling settlement in 1839, and identified himself with every stage of its wonderful progress until he left it a bright and brilliant colony in 1880'.

A portrait by J. Botterill is in the La Trobe Library, and another in the council room of the University of Melbourne.

Select Bibliography

Garryowen (E. Finn), The Chronicles of Early Melbourne, vols 1-2 (Melb, 1888); G. Blainey, A Centenary History of the University of Melbourne (Melb, 1957); J. V. Barry, The Life and Death of John Price (Melb, 1964); A. Sutherland, ‘Sir Redmond Barry’, Melbourne Review, 7 (1882); Redmond Barry papers (State Library of Victoria). More on the resources

Author: Peter Ryan

Print Publication Details: Peter Ryan, 'Barry, Sir Redmond (1813 - 1880)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 3, Melbourne University Press, 1969, pp 108-111.

DARLING, Sir CHARLES HENRY (1809-1870), military officer and governor, was born on 19 February 1809 at Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, the eldest son of Major-General Henry Charles Darling, sometime lieutenant-governor of Tobago, and his wife Isabella, the eldest daughter of Charles Cameron, sometime governor of the Bahamas. With a recommendation from Sandhurst, Charles joined the 57th Regiment as an ensign in 1826 and next year went with his regiment to New South Wales. He served as assistant private secretary to his uncle, Governor (Sir) Ralph Darling. In 1831 he returned to Sandhurst. In 1833-39 he served as military secretary to Sir Lionel Smith in the West Indies and in 1839-41 was captain of an unattached company. He then retired from the army and settled in Jamaica. At Barbados in 1835 he had married the eldest daughter of Alan Dalzell; she died in 1837 and in 1839 he married the eldest daughter of Joshua Bushill Nurse; she had one daughter and died in 1848.

Recommended by Lord Elgin, Darling was appointed agent-general for immigration and adjutant-general of militia in Jamaica in 1843 and became a member of the Legislative Council. He served as secretary to two governors, Major-General Sackville Berkeley and Sir Charles Grey, and in 1847 was appointed lieutenant-governor of St Lucia. In 1851 he married Elizabeth Isabella Caroline, the only daughter of Christopher Salter of Buckinghamshire; they had four sons. In that year he was transferred to Cape Colony as lieutenant-governor, and from May to December 1854 acted as administrator when parliamentary government was being established. His appointment as governor of Newfoundland in May 1855 was made permanent in February 1857. While in office he helped to inaugurate parliamentary government. He then served as governor of Jamaica, Honduras and the Bay Islands until 1863. He was appointed K.C.B. in 1862.

In September 1863, Darling took up duty as governor of Victoria. The governorship was one of the best paid and most highly prized in the empire, and Victoria appeared fortunate to have a governor with long experience of colonial administration and first-hand knowledge of parliamentary government. But the Colonial Office soon had misgivings about the wisdom of Darling's appointment. In his first year he became involved in the Australia-wide controversy over the continuance of convict transportation to Western Australia, and was privately censured by the secretary of state for the colonies, Edward Cardwell, for allowing his cabinet ministers too free a rein in their official dealings with the other Australian colonial governments. He was also rebuked for being a public, and thereby a partisan, supporter of the anti-transportation policy, but the matter was settled when the British government decided to end transportation within three years. The significance of this conflict lay partly in the close personal affinity which Darling had quickly established with his cabinet ministers, and partly in his eagerness to establish rapport with progressive colonial opinion. He soon became so personally involved in local political crises that he was unable to maintain the role expected of all colonial governors, that they should act as independent arbiters between contending factions in parliament and between social divisions in the community. He allowed his vice-regal authority to be used by the progressives as a bludgeon on the conservatives, and for this he was abruptly removed from office.

In the early 1860s Victoria was plagued by three controversial issues: reform of the crown land laws; proposals to change the customs tariff; and the parliamentary power of the pastoralists and free traders who dominated the Legislative Council. The council was elected on a property- and rurally-weighted franchise, whilst the Legislative Assembly was elected by manhood suffrage and represented the urban and working classes. Both Houses of the parliament had the power to accept or reject any new legislation. The McCulloch government, elected with a large majority in the assembly in November 1864, began to change the law in the three fields and provoked constitutional struggles with the council that brought chaos to the parliamentary system and involved the public and the press in controversy on an unprecedented scale. These important disputes between the progressive post-gold majority in the assembly and the conservative pre-gold majority in the council drew attention to the difficulty of grafting British parliamentary institutions on to a novel colonial society at a time when the British government, convinced of the virtues of free trade, was reluctant to make the colony completely independent especially in matters of manufacturing, trade and commerce. The disputes also made great demands on the governor's prudence and tact.

The council thwarted its own reform early in 1865 but the land issue was solved for the time being by Grant's Act of March 1865. However, the McCulloch government's attempt to introduce the first major protective tariff in Australia led to the main crisis. The assembly tacked the tariff bill to the annual appropriation bill, but the government had miscalculated the strength of feeling in the council where the bill was thrown out in July. With Darling's approval, the government continued to collect the new protective customs duties, relying on a resolution of the assembly. But the funds from the Customs House were inadequate to meet day-to-day administrative expenses, especially the need to pay the civil servants. The government then negotiated a series of short-term loans with the London Chartered Bank, whose sole local director was the premier. The bank then sued the Crown for the return of the money; by a series of court actions the government confessed judgment and the bank was repaid by vouchers drawn on consolidated revenue. The procedure incensed the council, the other private banks, the Argus and a large section of the commercial community. After a Supreme Court decision the government ceased to collect the new duties and seemed likely to be able to resist the council indefinitely. The assembly decided not to pass any appropriation bill until the council had passed the tariff. Darling tried in vain to arrange a conference between the two Houses, but in November the assembly sent up a separate tariff bill which the council promptly rejected. Thereupon Darling agreed to the government's request to dissolve parliament, and at the assembly elections in January 1866, the McCulloch government was returned with a two-thirds majority; the council, being indissoluble, retained its political complexion. After further disputes, another rejection of the tariff bill and the resignation and reinstatement of the McCulloch government, a conference was arranged in April and the tariff bill was eventually passed by both Houses of parliament.

Meanwhile in December 1865 twenty-two former cabinet ministers, who had served as members of the Executive Council, petitioned the Queen complaining of the financial and constitutional irregularities which Darling had permitted. When transmitting the petition Darling commented adversely on both the petition and the character of the petitioners and stated that it would be impossible for him to accept any of them in the future as cabinet ministers because he believed that they were conspiring to remove him. But Cardwell had already decided that Darling's actions had made him unfit for office; he was recalled to London and his successor appointed. Popular indignation over Darling's 'recall' was widespread. Petitions, public meetings and torchlight processions preceded the departure of 'the people's Governor', whom many believed had become a martyr in the cause of progress; others hinted that he was being sacrificed as part of a deal between the Colonial Office in London on the one hand, and the Legislative Council, the free traders and the pastoralists of Melbourne on the other. The assembly then resolved to make a grant of £20,000 to Lady Darling because the governor was not allowed to receive a direct gift. More constitutional crises ensued and Darling put his case to his superiors for the redress of his wrongs, on the ground that he had properly accepted the advice of his responsible advisers. But the response he received in the English press and in the British parliament was unsympathetic. Eventually the secretary of state informed Darling and the Legislative Assembly that Darling could not accept the grant. As a result Darling resigned from the colonial service in April 1867, and the Victorian government then included the grant in the annual estimates. The council rejected the appropriation bill. The McCulloch government resigned but was returned to office. A further appropriation bill was rejected by the council and the constitutional struggle now appeared interminable. A fresh assembly election merely reinforced the progressives in their determination to press the issue, especially as no alternative government was possible. Finally in May 1868 Darling was allowed to withdraw his resignation and in July was granted a retrospective pension. Broken in spirit and fortune he died on 25 January 1870 at Cheltenham, England. At his death a separate bill was passed by both Houses of the Victorian parliament, at the instigation of the McCulloch government, which granted a pension to Darling's widow and a sum for the education of her children.